From his hostel dorm-room recordings to emotionally charged visuals and lyrics that question cultural norms, Aksomaniac’s art is as intimate as it is powerful. In an exclusive chat with The Pioneer, the singer-songwriter opens up about his evolving relationship with music, queerness, and his upcoming Malayalam R&B EP Vartamanam

Tejal Sinha

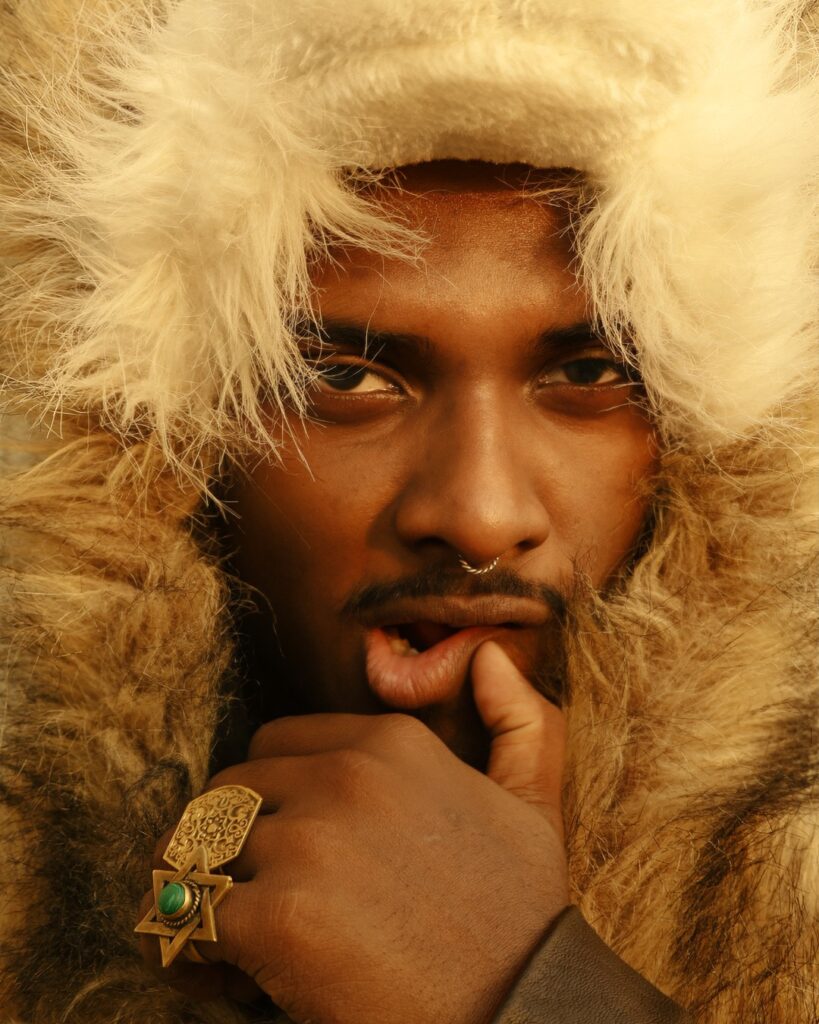

Aron Kollassani Selestin—better known by his moniker Aksomaniac—isn’t just creating music; he’s building a world. Rooted in vulnerability, resistance, and quiet rebellion, his songs unfold like deeply personal journals, stitched together by raw emotion and sonic fluidity. What began as a teenage online alias has now become the signature of an artist unafraid to blend genres, question norms, and explore queerness and identity through a distinctly South Indian lens.

The name, which he coined at the age of 14, combines the initials from his full name—AKS—with “maniac,” creating a handle that felt playful and personal. “There were no underscores or dots, so it looked clean,” he recalls with a grin. “Even though the music I make now doesn’t always match that silly, happy-go-lucky energy, I still want to validate that 14-year-old who was just having fun.”

The name may have started off as something close to a gamer tag, but today, it’s the alias behind a sonic journey that is deeply emotional, genre-fluid, and full of quiet resistance.

For Aron, music isn’t just about melody or form—it’s a form of journaling, a soft place to land. Growing up, he spent up to nine hours a day at the piano, forming a deep, almost sacred relationship with the instrument. “It became a safe space where I could be completely open,” he shares. “Some lines I’ve written didn’t mean much in the moment, but months later—after losing people or going through new emotions—I’d revisit the song and suddenly understand what I was really feeling back then.”

These delayed moments of emotional clarity, when he blushes or giggles at his own lyrics, are ones he treasures the most. “It’s like my own music teaches me about myself in hindsight,” he says.

Trained in Western classical music, Aron’s early approach to music was serious, almost scholarly. But over time, as R&B, jazz, and pop crept into his creative psyche, they awakened a playful side. “Once I understood the rules, it gave me a much bigger sandbox to be silly in—to play, break those rules, and make something personal,” he explains.

This willingness to blend and bend genres isn’t just aesthetic—it’s a metaphor for how Aron lives his life, navigating identity and queerness with honesty and grace.

Themes of queerness, vulnerability, and identity surface constantly in Aron’s music. His recent track Kanmashi is a potent example. “Even in Kanmashi, I’ve opened up about things I wouldn’t talk to my family about,” he admits. “There’s a certain safety in hiding behind your art form.”

That sense of safety, he believes, originated with the hours spent alone at the piano. “It felt like a private space, so that safety carried through when I started writing songs.”

While music offers him a protective layer, Aron is also slowly learning to be more open beyond his art. “I’m learning to be braver,” he says, “even when I’m not behind the piano.”

As someone who lives outside binaries—musically, personally, culturally—Aron isn’t interested in being neatly categorized. “I’m still trying to understand the decisions I’ve made—leaving home, quitting college for music, being open about my identity,” he says. “It’s overwhelming and blissful in equal parts.”

Rather than worry about public perception, he focuses on patience, kindness, and self-awareness. “I believe in being slow and patient in helping others understand who I am and what I’m trying to say, while I try to do the same.”

One of Aron’s most evocative songs to date, Kanmashi, explores themes of divine rejection, self-adornment, and transformation. “It really carries forward from what I said earlier—that overwhelming, blissful process of questioning and embracing,” he explains.

There was no single epiphany that sparked the track. “It was a slow burn. A process that took time to understand and even more time to write. Honestly, it’s just about being an early adult man—figuring yourself out, slowly and messily.”

The song’s visuals are equally striking—laden with cultural symbolism and lush intimacy. The music video, directed by Kaleido, emerged from a single line: “varamaai manmadan thazhukeedan.” “Manmadhan is such a culturally recognized symbol—it became a gateway into expressing the intimacy and the ‘taboo’ parts of the song,” Aron explains. Mythological motifs like Gandharva Vivaaha helped make the visuals resonate while retaining the core intimacy.

The details—jewelry, kajal—are deeply personal for Aron. “Kajal was actually one of the first things I ever put on my body as an act of self-assertion,” he shares. “It was about taking control of my perception—how I wanted to be seen.”

What’s especially poignant about Kanmashi is how it frames collapse not as failure, but as healing. “I’ve broken down structures built by myself and others—painful, but necessary to truly understand myself,” Aron says. “Sometimes, falling from grace forces you to face yourself up close.”

Moving to Mumbai after 21 years in Kerala was one such collapse—and one of the most transformative decisions of his life. “I wouldn’t trade that fall for anything.”

While Kanmashi is subtle in its resistance, Paapam is more direct—taking on the loaded idea of sin in the context of intimacy. “‘Paapam’ is about the feeling that lurks around intimacy—one with undertones of shame, guilt, and most importantly, sin,” Aron explains. “That comes from societal conditioning, where having autonomy over your pleasure is often frowned upon.”

For him, the “sin” in the song isn’t an actual wrongdoing—it’s the way culture has framed pleasure itself as a moral failure.

Interestingly, the word Paapam also carries different meanings across South Indian languages—ranging from sin to sympathy. “I didn’t play with that ambiguity intentionally,” Aron admits. “But I love hearing different interpretations—it’s beautiful when people take time to sit with it.”

The song was sparked by multiple moments—both personal and observed. “Taking autonomy over your pleasure can lead to difficult outcomes,” he says, “especially in a culture that suppresses healthy conversations around it.”

Musically, Paapam feels haunting and heavy, with a melody that practically invited the theme. “The fear around intimacy felt like the right narrative to stitch into that mood,” he says.

He’s candid about the dualities the song explores—indulgence versus regret. “There have been many moments where I’ve found pleasure in something, only to feel like I’ve done something wrong because I was raised to believe that,” he shares. “Paapam isn’t using metaphor—it’s a direct reflection of that experience.”

His ability to marry Indian melodic instincts with the sonic language of R&B, jazz, and blues gives his work a layered, hybrid soul. “It’s what I was brought up around, so it comes naturally. What’s evolved is how I’ve started harnessing that instinct through my affinity for hip-hop and Black music.”

Aron’s upcoming EP Vartamanam—which means both “conversation” and “the present”—is a bold, introspective exploration of identity. “Right now, I’m not even looking at other languages for expression—Malayalam feels like home,” he says.

The EP will feature a vibrant sonic palette: a dance track, a soft swing jazz piece, a pop-leaning cut, and of course, Kanmashi. “It’s a bit of a subtle pioneering moment,” he reflects. “I’m trying to understand what Malayalam R&B means for me—and what it can be going forward.”

Despite the lushness of his work, Aron doesn’t rely on pristine studios or curated rituals. “I used to live a double life—engineer by day, musician by night,” he shares. He’s written between college lectures, in hostel dorms, and more recently, amid the editing chaos at Jugaad Motion Pictures’ office.

“All of my music so far, including Kanmashi, was made in my Kerala government college hostel dorm room,” he says. “That’s far from an ideal setup. But if you have the drive to make music there, you can make it anywhere.”